A brief explanation of the science of mindfulness meditation, how meditation works from a scientific perspective, what psychology and neuroscience have to say about it, why it is meaningful to meditate regularly, and what happens in the brain when we do so.

Mindfulness meditation includes three components:

- Intention means, that we approach meditation with a certain purpose. While we meditate, we aim every moment to be purposeful or full of intention.

- Attention relates to the important aspect of training the mind to concentrate, to be attentive and aware, neither sleepy nor agitated. It also involves recognising mental distractions – or mind wandering. It means to let distractions go and in this way to self-regulate our mental states

- Attitude emphasises that we do so with a certain mental stance. During meditation we relate to experience with a non-judging, open, curious and accepting attitude.

Only when these three aspects are involved in the meditation practice would we call it mindfulness meditation.

This Intention-Attention-Attitude model has been proposed in 2006 by Shapiro et al. It also captures a key description that:

mindfulness is the awareness that arises when we pay attention on purpose in the present moment and non-judgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment to moment.

How mindfulness meditation works

When people start engaging with mindfulness meditation practice usually some practice in stabilising attention will be required because our mind has such a strong habit to focus on anything that arises. Our mind is quite wild and jumps here and there and everywhere. Our attention moves from one picture to the next, from one train of thought to the other, and on to another emotion, without peace, without stopping.

To keep our attention stable at one point is usually not something we are used to. We are only able to pay stable attention on one point because we are sucked in by what we pay attention to. Usually it is something that grabs our attention that is somehow very interesting, maybe a movie, maybe a football match, a video game an exciting book. Whatever it might be, it is so interesting and attracts our attention. In these situations, it is actually the power of the stimulus or the situation that pulls in our attention and gives us the impression that we can focus well.

However, attention during meditation is stable irrespective of the stimulation, independently of something exciting happening: just stable, clear, vivid attention.

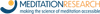

I developed a diagram that shows from a psychological and neuroscientific perspective what actually happens when we engage our attention in mindfulness meditation. If you look at the diagram below, you can see that it consists of three circles.

The inner circle: how we experience mindfulness meditation

The inner circle expresses our phenomenology. It expresses what we experience when we meditate. We can also say that it expresses the instructions we might receive from a meditation teacher.

It starts at the top here with focusing on an object. When we start meditating very often this object will be the breath, or more precisely the sensation while breathing. There are many reasons why the breath is a useful object, but this is a topic for another time.

At this point it is just about choosing an object and placing our attention on this object. This does not mean to analyse the object or to think about it. The object is merely a reference point or an anchor. Having such an anchor makes it easier for our attentional focus to stabilise. It also gives us a clearer indication, whether our focus is truly stable.

When doing this l at some point our mind will wandered off. This is expressed in the green part of the diagram. And then, sooner or later we will recognise that the mind wandered off, the red part. Then, expressed in orange in the diagram, we will let go of whatever our mind got attracted to. And then, as a final point (in green) we will return the focus of attention back to the object we wanted to focus on, let’s say the sensation of the breath.

The middle circle: Cognitive functions of mindfulness meditation

That’s a very simple circular process. And from cognitive psychology we understand all the attentional and cognitive functions that are involved in this process. These functions are depicted in the middle circle.

First of all, there is a function that we call sustaining attention. Here attention is stable and is sustained on an object. Then, sooner or later, distraction arises and then our cognitive monitoring function will detect that we have been distracted. This is followed by a further function, the disengaging of attention. It means to withdraw the focus of attention from the distracting object. We know from neuropsychological studies with brain-injured patients that this is a distinct function. It can be selectively impaired, particularly in patients who suffer from an injury in the right hemisphere. The next function is the shifting of attention back to the object back.

The outer circle: the involved brain networks

And now it gets even more interesting. From cognitive neuroscience we know that these five steps or cognitive functions are related to different brain networks. This is shown in the outer circle. The blue area on the top depicts the so-called Alerting Network. As the name suggests this network is involved in maintaining the level of alertness that allows us to sustain the focus of attention on an object.

The next network, here depicted in green, is the so-called Default Mode Network. This name is quite interesting. It is quite telling. Neuroscientists call it the Default Mode Network because we realised that our default mode is to be distracted. Our mind is quite distracted, busy with inner chatter: often with self-referential thought. From the neuroscience perspective we see this inner chatter as our default mode: when nothing else is going on, the inner chatter starts. I guess this does not come as a complete surprise, though.

Then there is a third brain network, Salience Network. It is sensitive for anything that is behaviourally relevant in a given situation. It gets activated when something appears that is particularly salient in a momentary situation. When we meditate with the clear intention to stay focused on the object, mind wandering – a distraction – becomes a particularly salient event.

As next step the Executive Control Network initiates the disengagement of the attentional focus from the distracting thoughts, followed by the Orienting Network, which reorients our attention back to the meditation object.

The brain networks are trained during mindfulness meditation

Now it is very helpful to understand that this circularity is actually pretty useful. Usually people new to meditation might think that getting distracted during the meditation is a problem, or even a failure. But if we understand the circularity, offers a different perspective: Every time we are distracted, we can practice the different components of this circular process in sequence. This means that the more often we are distracted the more often we can recognise that we are distracted. Thus, the salience network becomes active more often and the executive control network and the orienting network are also activated more often.

With every distraction that we detect we strengthen these networks. Through this repetitive process detecting, letting go, and reorienting of attention becomes more and more automatic. In consequence, the monitoring function – our ability to detect mind-wandering – will become more and more fine-tuned and sensitive. Also, over time fewer and fewer adjustments will be required. The whole process will become increasingly subtle and more and more stability will arise. This development depends on going through this circular process again and again.

Rather than seeing distraction during mindfulness meditation as a problem, it is our opportunity to practice, to strengthen our brain networks. We can thus enjoy every occasion where our mind has become distracted – at least if we recognised it and, of course, in an accepting, non-judging manner.

If you are interested in this diagramme – for professional or private use – download our free explainer pack.

Resources

- If you are interested in the diagramme, and related resources, check out my Explainer Pack

- The Intention Attention Attitude model: find a detailed explanation in our Knowledge Base

- Shapiro, S. L., Carlson, L. E., Astin, J. A., & Freedman, B. (2006). Mechanisms of mindfulness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(3), 373–386. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20237