Introduction and Overview

Mindfulness questionnaires belong to the standard toolbox of most meditation and mindfulness researchers. Scientists can choose from more than 20 different questionnaires and thousands of studies that used such questionnaires have been published. Here I offer my choice of the five best trait mindfulness questionnaires, underpinned by criteria for ranking them in this way.

Before going into the details, here my list of the five best mindfulness questionnaires:

1. FFMQ-SF | Questions: 24 | Factors: 5 | Sample Item: "Usually when I have distressing thoughts or images I can just notice them without reacting."

2. FMI | Questions: 13 | Factors: 2 | Sample Item: "I experience moments of inner peace and ease, even when things get hectic and stressful."

3. CAMS-R | Questions: 12 | Factors: 1 | Sample Item: "It’s easy for me to keep track of my thoughts and feelings."

4. PHLMS | Questions: 20 | Factors: 2 | Sample Item: "Whenever my emotions change, I am conscious of them immediately."

5. TMS | Questions: 13 | Factors: 2 | Sample Item: "I was aware of my thoughts and feelings without overidentifying with them."

What are mindfulness questionnaires?

Mindfulness questionnaires aim to estimate how mindful an individual is by asking respondents to rate to what extent different mindfulness-related statements apply to them, whether they agree with these statements or how often they experience a mental state described by these statements.

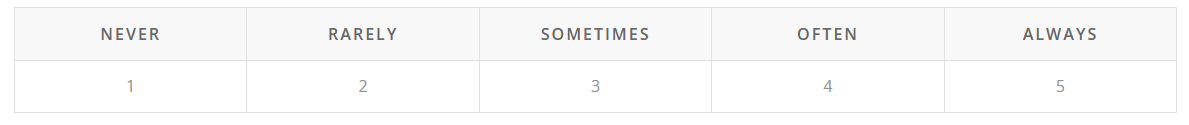

Respondents are usually asked to indicate their response by choosing from several options on a so-called Likert scale (pronounced like “Lick urt”). These Likert scales allow converting responses into numerical values that can, in turn, be subjected to statistical analysis. For instance, if a questionnaire asks about the frequency of an experience, response options and related scores may be:

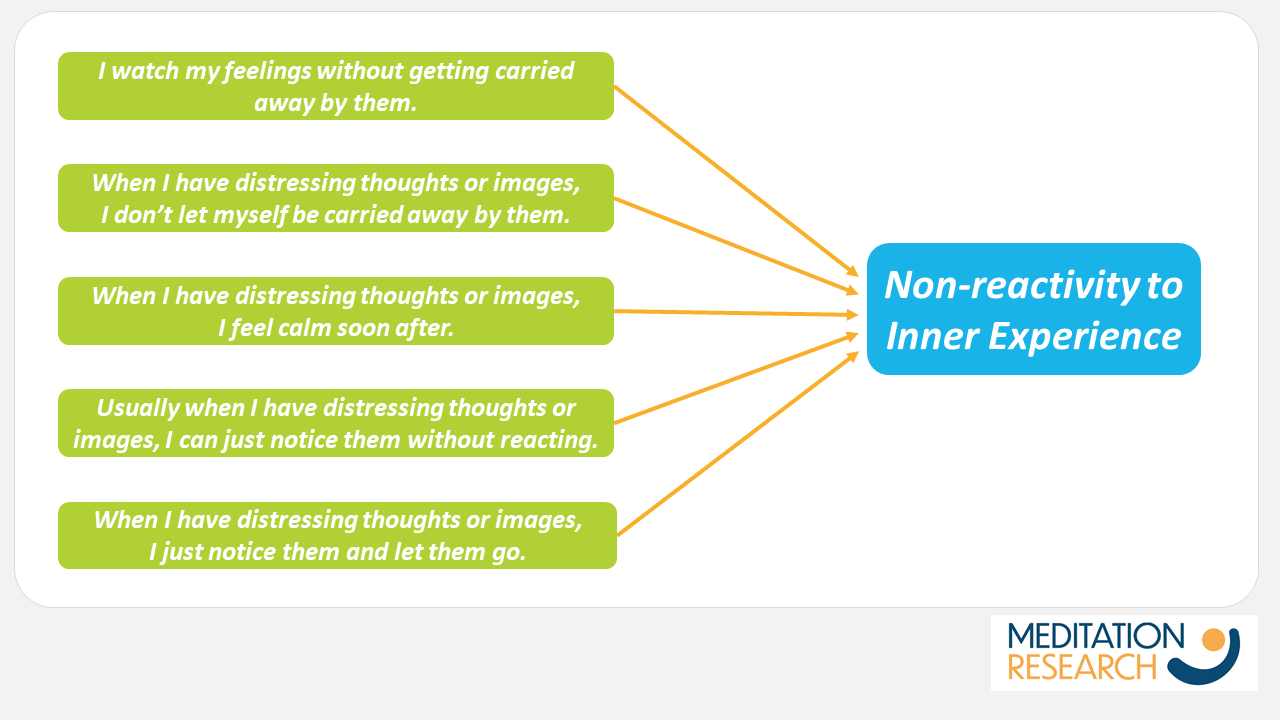

For a questionnaire to make sense, the different statements – or questionnaire items – need to reflect the construct or variable they are supposed to measure, in this case mindfulness. Usually, they do so indirectly. Rather than asking directly “How mindful are you?”, items probe experiences and behaviours that are thought to be an expression of mindfulness, or the lack of it. This means that based on the questionnaire responses researchers infer how mindful someone is, expressed as a numerical value. Accordingly, in the context of questionnaire research, mindfulness is called a latent variable or a latent construct, rather than something that is directly observed. The questionnaire items are called indicators.

To offer an example, the figure below shows the five indicators for the “non-reactivity” subscale of the FFMQ-SF.

Mindfulness as trait or disposition

Most frequently, mindfulness questionnaires are used to measure mindfulness as a trait, or disposition. Mindfulness is considered to be relatively stable aspects of an individual, sometimes also called ‘dispositional mindfulness’. In this sense, it is comparable to other stable psychological traits, such as the widely researched main five personality traits: Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism.

Rather than studying how mindful someone generally is, i.e. measuring mindfulness as a trait, other questionnaires measure how mindful someone is in a specific situation, mindfulness as a state. These state mindfulness questionnaires will not be discussed here, with one exception. The last questionnaire on my list, the Toronto Mindfulness Scale (TMS), offers two different versions, one measuring mindfulness as trait and another one as state.

For the link between state and trait mindfulness see an earlier blog post: From state to trait mindfulness

The importance of measuring mindfulness

Mindfulness questionnaires are used widely in meditation and mindfulness research to gain information how mindful the study participants are. Answering this question is often important. Think, for example, about the evaluation of all the different mindfulness-based interventions that are available. They are all called “mindfulness-based”, under the assumption that their main ingredients are exercises that increase mindfulness. Wouldn’t it be vital to know if this is indeed the case? Do mindfulness-based interventions really increase mindfulness?

And beyond figuring out whether this mindfulness label is justified, measuring mindfulness will also help to discover the mechanisms that make these interventions successful: What psychological processes contribute to increasing mindfulness? What psychological factors are influenced when mindfulness increases? These and similar questions can only be answered if we can measure how mindful someone is.

Why do we use questionnaires to measure mindfulness?

Science aims to be as objective as possible, with as little subjectivity as possible. To ensure objectivity, we would – ideally – prefer to not ask the subjects of our studies, the study participants. But there is no way around this subjective approach. However imperfect, it is the only way of gaining access to the experience of a person. We cannot see from outside how mindful someone is. We cannot just measure the brain activity of a participant to determine their levels of mindfulness. Somehow, when it comes to human experience, there is no way around asking participants.

Inherent problems of measuring mindfulness

The questionnaire approach, whether it is about mindfulness or anything else, has limitations. The answers participants give are necessarily subjective – we ask the participant to evaluate their experience – and in many cases respondents may not be fully aware of their experiences, they may have certain biases or may be inclined to answer in line with the expectations of the researchers. Also, respondents may understand and interpret questions in different ways. The latter is of particular concern for mindfulness questionnaires.

Indeed, research has shown that meditators and non-meditators understand the same mindfulness questions in different ways and may also evaluate their own experience in different ways. After all, to estimate how mindful I am, requires a certain degree of mindfulness. And a common impression of people who start engaging in meditation practice is that they seem to experience more distraction, that their mental states have become more unruly than they were before starting to meditate. In many cases this experience is a result of increasing awareness of one’s own mental states. Before one just did not recognise how unruly the mind is, because one did not focus on it.

This phenomenon is of particular concern when using mindfulness questionnaires for tracking meditation progress. When responding to questions about one’s own mental processes repeatedly, while the awareness of these processes changes, means that responses given at different time points cannot easily be compared.

Criteria for determining the quality of mindfulness questionnaires

Because questionnaires have been important tools in psychological research for a long time, we have well-established ways of assessing their quality, establishing their psychometric properties. Here some of the most important psychometric properties researchers rely on for establishing the quality of a questionnaire:

Questionnaire validity:

The appropriateness, meaningfulness, and usefulness of a questionnaire; whether it really measures mindfulness. There are many different aspects of determining the validity of a questionnaire, such as expert opinion or whether the questionnaire discriminates well between different groups, to name just two. In the case of a mindfulness questionnaire we would, for example, expect that in comparison to non-meditators, experienced mindfulness meditators score significantly higher. We would also expect that after completing a mindfulness-based programme, participants score higher than before.

Questionnaire reliability:

How reliable the questionnaire is as a measurement tool. Put simply, if we assume that a person has a fixed level of mindfulness, would the questionnaire always give the same reading? Think about a bathroom scale: For as long as my weight does not change, I would expect that the scale shows the same value each time I step on it. If it does not, the scale would have low reliability.

Researchers use different procedures to establish the reliability of a questionnaire, looking at it from different angles. One important aspect of reliability is called internal consistency. Internal consistency is a statistical way of expressing whether all items in a questionnaire – or a factor/sub-scale of a questionnaire – are consistent in what they measure, rather than only measuring vaguely related aspects. If the internal consistency is low, we cannot assume that all items measure the same construct.

Normative data:

Once a questionnaire is well-established (e.g. has good reliability and validity), it can be useful to accumulate normative data. These normative data are obtained from a representative sample of the population of interest. These data are then used to establish norms that indicate how people usually respond, or how the answers from one individual relate to the general population. Only when we have such normative data for a specific questionnaire it is possible to interpret responses for individual respondents. For instance, we would be able to answer the question whether a person is more mindfulness than the general population, or less mindful. At the moment (July 2020), there are no normative data for any of the mindfulness questionnaires.

What are the five best mindfulness questionnaires?

I considered the above quality criteria and a range of studies that investigated the quality of the questionnaires, sometimes with head-to-head comparisons, to arrive at my final list. So here are the five questionnaires that made the cut.

No 1: The Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire

No 1: The Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ)

The most widely used mindfulness questionnaire

- Includes five facets or sub-scales: observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judging of inner experience, and non-reactivity to inner experience

- Empirical evidence indicates that the analysis should primarily focus on the sub-scales. The use of an overarching mindfulness factor (“total mindfulness”) is less robust and should usually not be used

- A mix of positively and negatively worded items (some reverse-scoring required)

- Developed through a factor analytic study that pulled together five independently developed mindfulness questionnaires and extracted the 39 “best-performing” items to form the FFMQ

- The FFMQ has 39 items.

- Several short-forms have been developed – I suggest the 24-item version by Bohlmeijer et al. (2011). It is the most widely used sort form with the best psychometric properties.

- The FFMQ and some short forms have been validated in several languages

- See knowledge base entry for more details: Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ)

There is growing evidence that the ‘observing’ sub-scale has some problems and may nor always yield trustworthy results. Accordingly, sometimes researchers exclude this facet. Importantly, it appears that the ‘observing items’ are interpreted differently by meditators and non-meditators. If you want to track how mindfulness develops when beginners start engaging with mindfulness meditation (e.g. before and after an MBSR course), this will be problematic.

Key reference:

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self- report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27-45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191105283504

No 2: The Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (FMI)

Particularly useful for assessing mindfulness developed through meditation practice

- Includes two sub-scales: presence and acceptance

- Should always be used as two-factor version, not combining the two factors

- A 13-item short form (FMI-13) appears to have better psychometric properties than the earlier 14-item short form or the original full version

- has good psychometric properties and is widely used

- See knowledge base entry for more details: Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (FMI)

The FMI could also appear in the first place. It is a joint first with the FFMQ. Whether you want to use the FFMQ-SF or the FMI-13 will primarily depend on a question whether you want to focus on a fine-grained analysis of mindfulness facets (then use the FFMQ-SF) or whether you are particularly focusing on mindfulness developed through meditation (then use the FMI-13).

Key reference:

Walach, H., Buchheld, N., Buttenmüller, V., Kleinknecht, N., & Schmidt, S. (2006). Measuring mindfulness—the Freiburg mindfulness inventory (FMI). Personality and individual differences, 40(8), 1543-1555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.11.025

No 3: Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale - Revised (CAMS-R)

Based on the most-widely applied/accepted conceptualisation of mindfulness (e.g. Bishop et al. 2004)

- integrates key aspects of mindfulness and yields one total mindfulness score

- good psychometric properties

- 12 items

- Although the scale is labelled as ‘revised’, the original CAMS was never fully published

- Translations into several languages have been published

- See knowledge base entry for more details: Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale; Revised (CAMS-R)

Key reference:

Feldman, G., Hayes, A., Kumar, S., Greeson, J., & Laurenceau, J. P. (2007). Mindfulness and emotion regulation: The development and initial validation of the Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised (CAMS-R). Journal of psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 29(3), 177-190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-006-9035-8

No 4: Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale (PHLMS)

Not as frequently used as the first three questionnaires; captures the two key components of mindfulness

- Captures the two key components of mindfulness as separate, independent factors: present-moment awareness and* acceptance*

- It is worth noting that these two factors are truly independent of each other, thus measuring unrelated constructs

- 20 items; 10 per sub-scale

- Available in several translations

- See knowledge base entry for more details: Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale (PHLMS)

Key reference

Cardaciotto, L., Herbert, J. D., Forman, E. M., Moitra, E., & Farrow, V. (2008). The assessment of present-moment awareness and acceptance: The Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale. Assessment, 15(2), 204-223. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191107311467

No 5: Toronto Mindfulness Scale (TMS)

A frequently used questionnaires; trait and state versions available

- Conceptually, the TMS is similar to the PHLMS (no 4 on my list)

- a frequently used mindfulness questionnaire

- State and trait version available

- Items of the state and trait version are similarly phrased

- Both versions have 13 items

- Includes two factors: Decentering and Curiosity

- While the two factors of the PHLMS are truly independent, the two factors of the TMS somewhat overlap (what is not uncommon for mindfulness questionnaires)

- All items are positively worded

- Translations into a few languages are available

- See knowledge base entry for more details: Toronto Mindfulness Scale (TMS)

Key Reference

Lau, M. A., Bishop, S. R., Segal, Z. V., Buis, T., Anderson, N. D., Carlson, L., … & Devins, G. (2006). The Toronto mindfulness scale: Development and validation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(12), 1445-1467. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20326

Questionnaires that did not make the cut

I am not going to list all the questionnaires that did not make it. In the Meditation Research Knowledge Base, I list all the 20+ mindfulness questionnaires that are available and that I considered.

But as some of you may be surprised that the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS), developed by Brown and Ryan (2003), is not on the list, a few words about this popular questionnaire. As I explained in a Knowledge Base entry, and in line with several other researchers, the MAAS is not well suited as a complete mindfulness measure because it only captures one aspect of mindfulness (the attention aspect of awareness) and, by design omits the attitudinal component. Brown and Ryan clearly state:

“The MAAS is focused on the presence or absence of attention to and awareness of what is occurring in the present rather than on attributes such as acceptance, trust, empathy, gratitude, or the various others that have been associated with mindfulness.” (Brown & Ryan, 2003, p. 826)

Most mindfulness/meditation scholars agree that the non-judgemental and accepting quality of awareness is crucial for mindfulness. Thus, if the aim is to capture mindfulness in the sense of non-judgemental moment-to-moment awareness of arising phenomena, the MAAS will only tell half of the story.

I also did not include questionnaires that aim to assess the quality of teaching mindfulness, nor questionnaires that are based on different conceptualisations of mindfulness, in particular the Langer Mindfulness Scale, which operationalises Ellen Langer’s socio-cognitive perspective of mindfulness.

Developments to watch out for

Scholarly work to improve the quality of mindfulness questionnaires is ongoing and it is certain that we have not yet arrived at the best ways of measuring mindfulness. we may thus cast our eyes forward to a few promising developments.

BIMS

Nicholas van Dam, working at the University of Melbourne, is spearheading the development of the Balanced Inventory of Mindfulness-Related Skills (BIMS). The BIMS is seen as an improvement on the FFMQ. The authors revised the content of some FFMQ items and changed how the participants need to respond: In the structured alternative response format, participants rate which of two alternative statements is more like them, and to what extent it is so.

Participants have six response options: between “very characteristic of me” (1) and “a little characteristic of me” (3) for the statement on the left or between “a little characteristic of me” (4) and “very characteristic of me” (6) for the opposing statement presented on the right. The result of this development work is a 22-item questionnaire that offers a general mindfulness score and four factor scores: Acting with Awareness, Describing, Non-Judging of Experience, and Non-Reacting to Inner Experience.

This looks like promising work and I will keep a close eye on how this develops.

Decentering

The concept of decentering is gaining traction. In a recent review, Bernstein et al (2015) describes it as the mental state where a person relates to their own subjective experience of the world as a “third-person observer”. They see decentering as the inherently human capacity to shift the experiential perspective from being engrossed to being a “neutral” observer.

Within the influential Intention-Attention-Attitude model of mindfulness, the main result of mindfulness meditation is described as reperceiving (Shapiro et al, 2006), a construct closely aligned with decentering. Currently, the Experiences Questionnaire by Fresco et al (2007) is the prime questionnaire for assessing decentering. As summarised in Bernstein et al. (2019), several new developments for measuring decentering are under way.

Breath Counting Task

The Breath Counting Task is a recently developed “behavioural tool” that aims to measure mindfulness without having to use a questionnaire. (Levinson et al, 2014). During this task, participants are asked to count their breaths from 1 to 8 and press one button for each breath. On the ninth breath they are to press another button. In addition, they were instructed to press a further button to indicate that they lost count, so-called self-caught miscounting, and then to restart the counting with the next breath.

- Levinson, D. B., Stoll, E. L., Kindy, S. D., Merry, H. L., & Davidson, R. J. (2014). A mind you can count on: validating breath counting as a behavioral measure of mindfulness. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1202. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01202

- Wong, K., A. A. Massar, S., Chee, M.W.L. et al. Towards an Objective Measure of Mindfulness: Replicating and Extending the Features of the Breath-Counting Task. Mindfulness 9, 1402–1410 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0880-1

Some initial studies confirm that the skill in breath counting may be a good behavioural measure of mindfulness. Currently more research, including our own, is ongoing to establish how useful this new tool might be.

Experience sampling methodology

Rather than asking participants to look or think back and make a retrospective evaluation of their experience and behaviour, experience sampling methodology makes use of smartphones (in the old days also pagers, notebooks and similar devices). Participants are prompted at quasi-random times to answer a few questions about their current experience. In terms of assessing mindfulness, this approach is still in its infancy, but some interesting developments, including our own research, are on their way.