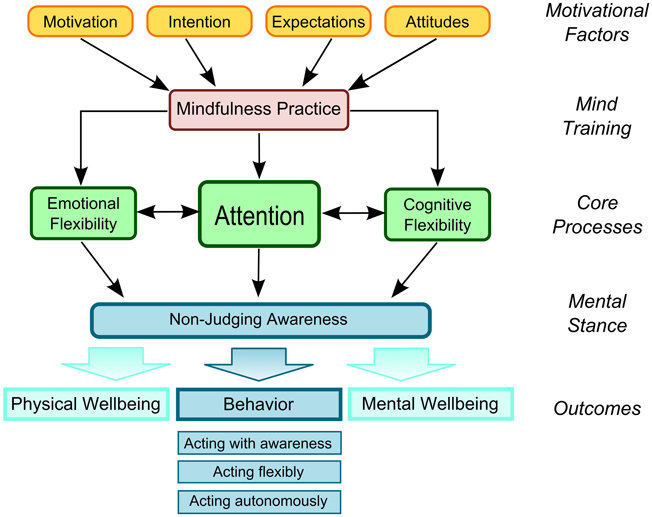

n my recent review paper on attentional control mechanisms in mindfulness meditation I also presented our Liverpool Mindfulness Model. The main purpose of this model is to serve as a structuring aid for our own meditation research. It is thus more of an outline of the different aspects that should be considered when studying mindfulness practice – or, if you want, even a wish list of all the things we would like to investigate. When drawing up this model I tried to be frugal and only included the most crucial aspects, while leaving out many other components. Every ‘box’ in this model can be further subdivided into many more fine-grained aspects and every arrow that is present warrants a whole research programme, not to mention all the other ‘missing’ arrows that would outline further interrelationships.

Having said all that, the model nevertheless makes a few important points. First of all, it considers attention as the central core processes. Without refining our attentional skills and developing the ability to maintain a stable focus of attention for some time, a profound development will be difficult. However, the term ‘attention’ is meant to capture something much broader, including for instance attentional control mechanisms, which include an awareness of one’s cognitive and emotional states and the resulting ability to respond to them in a flexible way.

This attentional, emotional and cognitive flexibility gets a specific flavour when it is combined with a certain mental stance, perspective or view – and this is expressed here as non-judging awareness, the ability to be aware of the various mental states without being caught (out) by them, but rather being able to maintain an open presence. These two aspects of attention and awareness are considered the two main contributors when developing a mindful approach to one’s life. However, in line with other colleagues (in particular Shapiro et al., 2006 and Wallace & Shapiro, 2006) we think that it is crucially important to also consider what brings people to being interested in and willing to practice mindfulness – all the emotional factors. Similarly, it will be important to consider the outcomes in terms of physical and mental wellbeing but also – and this has so far hardly been considered – in terms of behavioural outcomes. The model mentions here three descriptors that qualify ways of acting in an aware, flexible and autonomous fashion. These three qualifiers (and probably a lot more) could then be applied to various specific fields of activity.

In our own research we are, for example, interested in eating behaviour, where pilot data from a mindful eating intervention we developed suggest changes in actual eating behaviours. In this example we can see all five levels involved: Participants take part in the programme because they are interested in a healthier approach to food and eating (1 – motivational factors), they engage in the mindfulness practice (2 – mind training), they develop their attentional, emotional and cognitive abilities (3 – core processes) and their ability to maintain an open awareness to the different food- and eating-related impulses, desires and cravings (4 – mental stance) and finally higher mental wellbeing (e.g. less eating-related anxieties or feelings of guilt), higher physical wellbeing (e.g. weight loss and related benefits) and more choiceful eating behaviours result (5 – outcomes) result from it.

Although the practice of mindfulness is conceptually incredibly simple (“Just focus on the sensation of your breathing and maintain a non-judgemental, open awareness of all arising mental events”), if we look a bit closer, it entails a whole range of aspects that influence and are influenced by this practice. Because the practice aims at some of the most central aspects of our conscious awareness – attention, emotion, cognition) the effects it has can be as far-reaching and wide-spread as the rapidly evolving research and the practical applications suggest.

References

- Malinowski, P. (2013). Neural mechanisms of attentional control in mindfulness meditation. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 7, 8.

- Shapiro, S. L., Carlson, L. E., Astin, J. A., and Freedman, B. (2006). Mechanisms of mindfulness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62, 373–386.

- Wallace, B. A., and Shapiro, S. (2006). Mental balance and well-being: building bridges between Buddhism and Western Psychology. American Psychologist, 61, 690–701.